Some Oxford Classical Texts really need a table of contents. Perhaps most of all Ausonius, whose works are numerous, of widely-varying length and interest, and numbered differently in just about every edition. I suspect that few Latinists have ever had the urge to sit down and read any of the editions through without skipping: surely we all pick out specific works to read based on recommendations and references. Riffling through the OCT to find the Parentalia or Epigrammata or Mosella doesn’t take long, but if you’re looking for Cupido Cruciatus, or Bissula, or Griphus Ternarii Numeri, or the Pseudo-Ausonian De Rosis Nascentibus, it can take a while, and these four short works are among the most interesting in the volume. There is a concordance of numerations in different editions (286ff.) but it doesn’t give the titles, so it only helps if you already know the number in another edition. The Index of proper names and related adjectives (299-316) does help, since the only ‘Bissula’ listed is in the collection Bissula (work XVII), and (much more surprising) the only ‘Cupido’ is in Cupido Cruciatus (work XIX), but an actual table of contents up front would be much better, not only in principle but in practice.

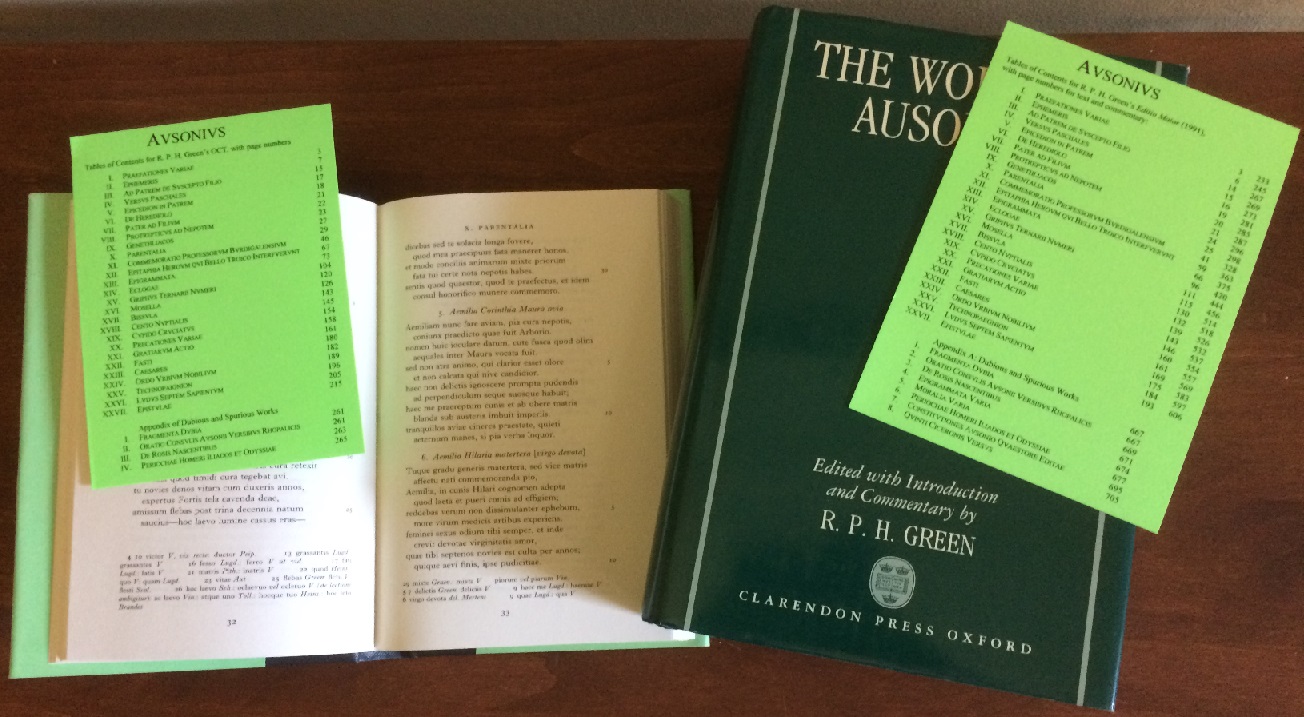

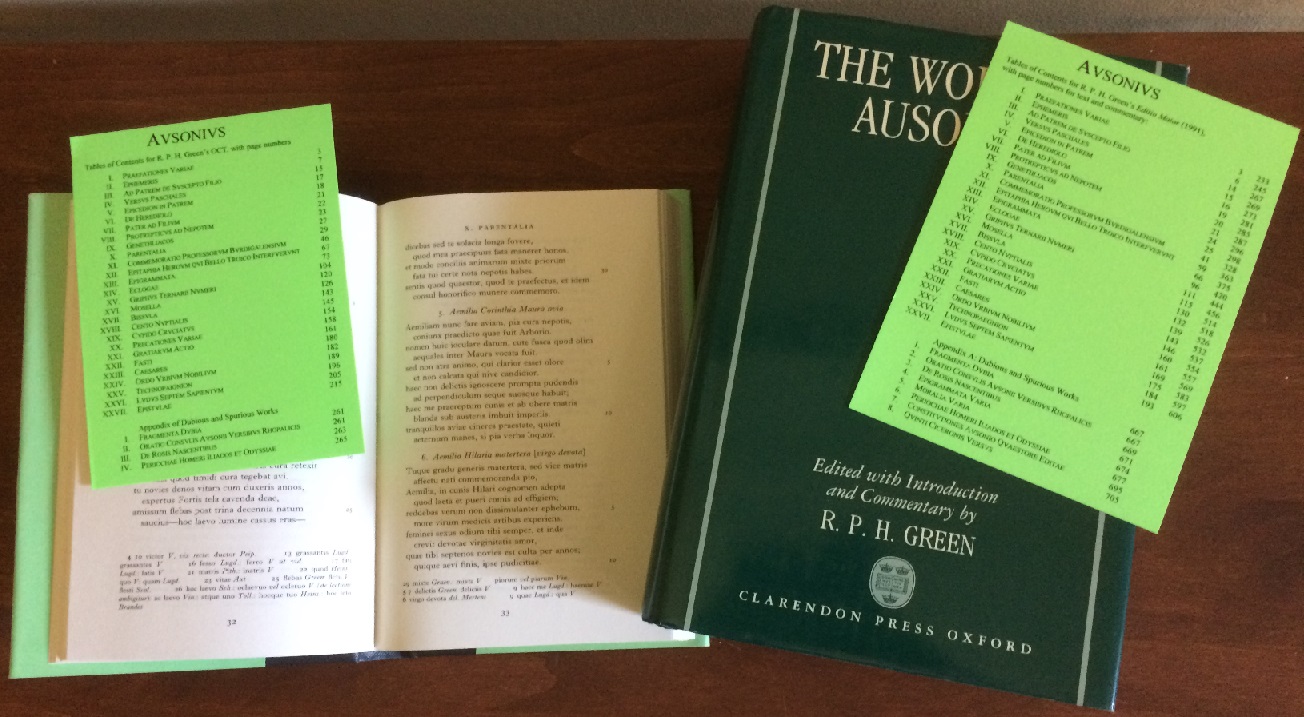

To solve this minor, but annoying problem, at least for Ausonius, I have made my own table of contents file. In fact, I made two files, one (link) for R. P. H. Green’s OCT (1999), the other (link) for Green’s previous editio maior (Oxford, 1991), which is in the same order, but contains a few more spuria at the end and has different pagination. For each, I give the pagination in the right margin, in two columns (text and commentary) for the editio maior. In each file, I also give a second version, sorted alphabetically by title, for those who prefer it.

Please feel free to print these out for your own use, adjust the print size for readability, and also to edit or resort them if (e.g.) you prefer to put De Rosis Nascentibus under D rather than R in the alphabetical list, and Ad Patrem de Suscepto Filio under A rather than P.

I used green ‘cover stock’ to make mine, which means they will probably outlast me, even unlaminated, and make useful bookmarks. Here’s a picture:

As for the general question raised in my title:

Many (most?) OCTs and Teubners and Budés need no table of contents. In a one- or two-volume Iliad or Odyssey, no reader will be in doubt as to where a particular passage will be found, though some will curse the OCT for having the running book-numbers in the headers in Greek alphabetic notation, so you have to remember that Book 14 is Ξ (ξ in the Odyssey) and Ξ or ξ is 14. However, even chronologically-ordered Euripides can be a problem if you don’t have the dust jackets. I can never remember whether Hecuba is in volume I or II, Ion in II or III. Do the modern greasy-feeling plastic-covered no-dust-jacket not-sewn-in-signature OCTs list the names of the included plays on the covers, which otherwise mimic the older dust jackets? I note that Kenney’s OCT has ‘Ovidi Amores Ars Amatoria Remedia Amoris’ printed on the spine of the book itself (one word per line), but doesn’t tell you that it also includes what’s left of the Medicamina Faciei Femineae, tucked in between Amores and Ars, though ‘Medicamina’ would have fit unhyphenated. (I wonder how many others ever noticed, and how many of those cared.)

Next: Part II. Which OCTs and similar texts really need a table of contents?

After that: Part III. Why don’t OCTs and similar texts always print their contents in chronological order when this is known?

Five More Seneca Commentaries

I have been intending to update my list of commentaries on Seneca’s Epistulae Morales, especially since Jeremias Grau told me in a comment on my last update about three I did not know: two German PhD theses (one of them his own) that will be published as books in the next year or two, and a recent commentary on letter 104 that I had missed (Lemmens 2015). I have now (six months later – oops) added these three, plus two more, one that just came out (Li Causi 2019) and one that I had unfairly neglected (Trapp 2003). Pietro Li Causi’s is a collective commentary on 124, written with his students, only available as a free on-line PDF, which I know from John Henderson’s review in BMCR. Michael Trapp’s is the Cambridge ‘green and gold’ collection of Greek and Roman Letters, which includes detailed notes on two short letters (38 and 61) and the opening of a longer one (75.1-5), all three relatively neglected by full-time Seneca commentators.

If anyone knows of others I have missed, please let me know: I have a feeling I may have seen one more. The number of letters that get no love from any commentator or translator of selected letters is now down to eight, or will be when the three dissertations at the end of my bibliography come out in book form: 45, 69, 74, 81, 89, 98, 109, and 111. If someone is looking for a thesis topic, one or more of these would make a good one.

As I mentioned in my last update almost a year ago, some day I hope to find the time to transform my list of Seneca commentaries into a data base for easier and more flexible searching, allowing users to sort the bibliography by date (as it is now) or alphabetically, or to filter the results to include only one or a few or a range of letters, and to filter commentaries by language, or by level (scholarly vs elementary), by whether they include text, translation, both, or neither, and so on. If I’ve forgotten any important criterion for sorting or filtering, please let me know.